I was prepared to be critical of The Substance (2024). Sometimes it’s like that. You get too in your head about what it all means and find yourself sitting in the movie theater seat haughtily sipping Diet Coke, eye-rolling at the opening credits.

The film I was ready to be unimpressed with, is, in brief, about a 50-year-old Jane Fonda-esque exercise video star named Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), who takes an illicit drug called “The Substance” that allows her to spend seven out of 14 days in the body of a younger version of herself (Margaret Qualley). Sparkle abuses the drug, of course, which leads to the extreme deterioration of her body.

Even in my overly analytical state, I was ultimately, and thankfully (isn’t it nice to enjoy things?), won over by The Substance, and I can pinpoint the exact moment when it happened: Sparkle, in her 50-year-old form, is attempting to go on a date but cannot bring herself to leave her apartment. She keeps returning to the mirror, reapplying makeup and upping the ante of her outfit to be first more and then less revealing. Finally, in lipstick and a cleavage-covering scarf, she puts her hand on the doorknob, but like poor Lot’s wife, she turns back. Leering through the penthouse window is a comically large billboard featuring her younger replacement in a cut-out pink leotard. The billboard is so absurdly imposing that it could only have been intentionally absurd. I felt as if I were locking eyes with writer, director, and co-producer Coralie Fargeat: I had to surrender my defenses; I saw what she was doing.

Again, I am among the majority of viewers who thought The Substance was “good” (though I do not think it earned its two-hour-twenty-minute runtime). That said, I’m no arbiter of taste, and I’m willing to take in opinions counter to mine. Maybe there’s something I missed or an argument that might allow me to see the art anew. True to form, the internet had no problem delivering adverse takes.

The first review I’ll reference here appeared in Slate and is written by Dana Stevens; the second is by Emily Gould for The Cut. Both writers felt the same about The Substance: They hated it.

Neither piece of criticism convinced me fully of its writer’s central objections, but Stevens put up a good fight. She acknowledges that The Substance “evokes… all enduring classics of the horror genre,” and is backed by relevant references to that point, though she ultimately concludes that the film disappoints in terms of “intellectual heft.”

“After two hours and 20 minutes of flamboyantly repulsive variations on this well-worn theme, even the strongest-stomached and most feminist of viewers could be excused for muttering, We get it already,” Stevens writes.

Personally, I saw the film’s knock-you-over-the-head symbolism and plot simplicity as purposeful; fablistic rather than realistic—a response that Stevens deftly anticipates, when she writes “Fans of The Substance may object that her bluntness is a deliberate style choice, and the filmmaker would no doubt agree.”

I am interested in criticism as an investigation of choices. Stevens attempted to view the film from a perspective beyond her own; she sought to understand the director and writer’s intent, and based her judgment of the film’s merit on a range of externalities and viewpoints.

Gould’s article, on the other hand, does none of that. Instead, she comes to the ironic conclusion that because Demi Moore is “one of the most beautiful 62-year-olds on the planet” it’s not believable that she would “sacrifice everything to allow a glistening Margaret Qualley to burst forth from [her] spinal column.” She ignores, or is oblivious to, the fact that it is precisely because people think that Moore/Sparkle is so beautiful that she is willing to risk everything to maintain such acclaim.

Several times, Gould asserts that Moore/Sparkle—because, in talking about Sparkle, we’re also entering into a meta-narrative about the famous woman playing her—“looks fantastic,” and that, naked, “she looks great, thin and lithe with preternaturally pert boobs and just the tiniest bit of normal-human ass-sag.” Why, oh why, Gould asks, would someone whom I believe to be so beautiful, take such a massive risk? In making her point, I argue that Gould becomes a real-life representative of the capricious, culturally ingrained beauty standards the film attempts to puncture.

If I understand her argument correctly, Gould doesn’t find the film believable partly because she doesn’t see how someone like Moore/Sparkle could consider herself ugly. She wanted more realistic proof that Elisabeth Sparkle is aging: “What a thoroughly chilling—because familiar—moment it would have been to have Elisabeth notice some minor change in her pristine appearance, a stray, unruly gray chin hair or the shock of a vein protruding on an otherwise smooth thigh?”

Sure, Sparkle looks in the mirror all the time in The Substance, and the reflection, to the vast majority of us, is stunning. But her beauty has never been a matter of the image in the literal mirror. The reality of her beauty lies in the amorphous, conceptual world of public opinion—a warped mirror. Gould seems to forget that there is no such thing as beauty; that Demi Moore is “beautiful,” is a subjective opinion, as absurd as that may seem. Without getting too existential about it, beauty doesn’t exist in the same way that a cup or a chair exists (I’m not going to go so far into existentialism as to question the reality of objects); it’s a concept that humans have invented and reinvented over time. When Sparkle is being showered with praise for her beauty, she believes that she is beautiful. When her producer Harvey (played by the magnificently disgusting Dennis Quaid), fires her from her job for being too old, she believes that she is too old. When she overhears Harvey saying that she’s washed up, in her world that means, definitively, that she is washed up, because what men like Harvey have said about her has always been the pivot upon which her success, and her life, depends.

When Gould writes, “The process of aging naturally is disgusting, this movie seems to be saying,” she is at once missing the point and making it. The point is that we think Demi Moore is age-defyingly beautiful. The point is that she doesn’t have gray chin hairs or varicose veins. The point is that beauty is fickle; it can be denied even when it seems obvious to the rest of us. Sparkle does not see her own worth because her self-worth is based only on feedback. That Moore is considered a paragon of ageless beauty, is, I think, essential to the film’s premise. And if there is a larger moral, which Gould seems to want, I would argue that it’s the exact opposite of what she suggests: The process of “aging naturally” would be far preferable to the fate that befalls Sparkle by the film’s end, in which she is rendered physically monstrous. Importantly, in this final act, it is only Sparkle’s body that has transformed; in a sense, her body is only catching up to her brain, which remains as disfigured as it was in act one. No matter how beautiful we think the actress playing Sparkle is, she begins and ends the film as an “ugly” monstrosity, a being with no intrinsic sense of purpose, no family or friends, nothing to live for but the shallow adoration of a fickle public and a rotten industry.

I have little interest in lambasting writers, especially good ones!, so apologies to Gould. I’m now going to jump into a larger point about film criticism, namely horror criticism:

I’m not typically interested in assessing whether a movie is good or bad. But I do read reviews, clearly. When review-oriented film criticism is at its best, the writer is well aware of the context in which a film is made, the references a director or writer is attempting, and the genre in which the film is operating—its rules, tropes, and history. When it’s at its worst, the writer is viewing a film in a vacuum, making assumptions about what a director is attempting to say or do without investigating those assumptions further.

As I wrote recently, I find that people issue the least worthy opinions about horror movies when they aren’t in on “The Joke”—The Joke being that believability and unpredictability are not necessarily the point. To put it another way: Market value refers to the rule of supply and demand in capitalism; the price of something is determined by what people are willing to pay. Horror operates similarly: The believability of a film is entirely dependent on what people are willing to believe. And horror audiences are willing to believe quite a lot. So the market value of a horror film is not about whether it’s realistic; in fact, it’s often the opposite. The market value of a horror film is often whether the film earns its unreality.

Because it’s a genre that has not received much critical respect in the past, much of the film criticism reaching the mainstream comes from people who just aren’t in on The Joke. It is from reviewers like these that we get the term “elevated horror,” which I find a tad reductive, since most “elevated” horror filmmakers, like Jordan Peele, readily acknowledge the influence of the genre’s less “elevated” stalwarts. (Sidenote: It’s nice to see FFTW and IRL friends like Kellina Moore breaking into mainstream pubs like the New York Times).

To be clear: I’m not using The Joke terminology to refer to horror comedy. I’m talking about the language fans and creators speak amongst each other, on-screen and off, and I guess I think of this language as a joke because, like laughter, it is a way of processing the anguish of having a body and a consciousness. In my mind, horror has always been a kind of wry smile shared between two people who know they are hopelessly fucked.

Many people are put off by horror’s schlocky, over-the-top gore and brutality. Someone outside of, or opposed to, the genre might be aghast at what horror fans discuss: Cheering for particularly gruesome, well-played “kills,” for instance, hungrily anticipating the death of the virgin, complaining that a murderer is not murder-y enough. In a vacuum, this is disturbing stuff. But we’re not operating in a vacuum—we never are. And that’s what The Joke is: An acknowledgement that we’re inside of an elaborate set-up, one that’s been built up and renovated over years, and is judged by how well a filmmaker can get us to the punch line.

In that sense, horror is a little like “The Aristocrats,” a literal joke form which many comedians have iterated on, including Robin Williams, Bob Saget, and Sarah Silverman. The fundamentals of “The Aristocrats” are always the same: a family auditions for a talent agent by performing a series of vile, incestual acts. The punch line matters naught, since it’s implicit in the title. The comedy isn’t in the originality of the premise, but in the originality of the delivery.

Similarly, horror is a genre particularly laden with in-rules and recognizable tropes. The most famous is the concept of the “Final Girl,” coined by Carol J. Clover in her seminal text, “Men, Women, and Chainsaws.” The Joke in horror is often about how a filmmaker works within those themes, by molding to them, inverting them, or, as is the case in meta horror like Scream (1996), directly referencing (and even critiquing) them.

A final point: Part of what people find distasteful about horror is its tendency to veer into torture porn. This is the stomach-turning “we get it already” reaction that Stevens evokes.

Terrifier 3 (2024) came out recently, a franchise that has boomed since its first film, thanks primarily to the eeriness of its central villain, Art the Clown. In discussing the film, Henry Zebrowski, of “Last Podcast on the Left,” issued what I think is an apt analysis of what differentiates horror sub-genre “torture porn” from plain old torture:

“[My issue with] essentially, torture porn, is when it’s realistic and not entertaining; when it literally is just torturing someone in a realistic fashion and it’s just crying and screaming and there’s nothing else going on… there are things that [Art the Clown] is doing that humans just cannot do… On that level while it’s a horrific sight, it’s also so, so over the top that it really—it’s, art.”

That “over the top” quality is part of The Joke; it’s what allows us to laugh at murder. It’s what both reviewers seem to dislike about The Substance; they wanted it to be “realer,” more “believable.”

In this case, by “real,” they mean more subtle, but some people seem to think the move toward reality happens in the opposite direction. I am opposed to horror films that feature real-life deaths, like Cannibal Holocaust (1980) which sacrificed multiple animals in its making as well as traumatized many members of its cast. In my opinion, these films abuse a tacit agreement between audience and creator. It’s similar to the backlash that occurs when comedians like Louis C.K. reveal that they have actually been committing the heinous acts they riff about on stage. We had been led to believe that we were in on The Joke. When the fourth wall is broken, and The Joke is revealed to be not a joke at all, we are rightfully upset to realize that we’d been laughing the whole time.

There is a massive difference—one might say a critical difference—between snuff and art. Art is a line that separates the real from the contrived; I believe it is a skill to respect that line while appearing to blur it. And it is the critic’s responsibility to inspect the decisions artists make as they perform this tricky routine, why they do or do not choose believability, or subtlety, or sincerity as a goalpost.

In case I’m sounding too sanctimonious, here’s some self-critique: I didn’t care for I Saw the TV Glow (2024). Had I written an off-the-cuff review of it, I would have written a bad review. But then I talked to a friend more cinematically attuned than I am, and he explained the references that had gone over my head. For instance, in one scene, two men arrive at the protagonist’s doorstep and are never explained or referenced again. He told me they were from the ‘90s Nickelodeon show “The Adventures of Pete & Pete.” The idea that comforting characters from our childhood might appear in twisted form is essential to the film; once I understood the choice, I had more respect for the result.

A meaningful piece of film criticism would account for the casual viewer and the more knowledgeable viewer alike. Through more knowledgeable eyes, I understood the film’s value much differently. I understood the context in which the film was made, and I was willing to give it another shot.

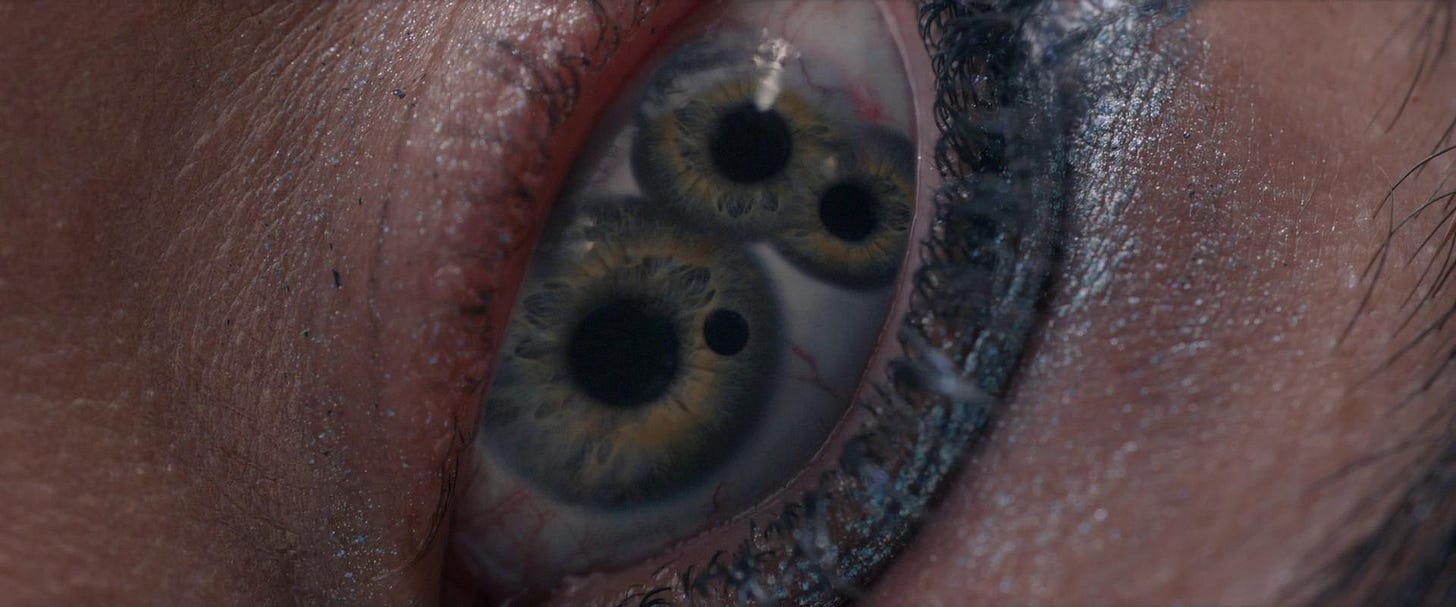

That’s the beauty of what a talented critic can do: They can open your eyes. Taking a sincere stab at writing about art requires seeing something once, for ourselves, and then seeing it differently, from a multitude of angles; viewing the piece of art as if through a kaleidoscope, rendering it more beautiful and more complex than it seemed on first glance. You can still do this and come to the conclusion that it sucks, but at least you’ll have earned that conclusion.

This practice is beneficial for the critic, too. In the workshop setting, we're expected to examine a piece of writing in the context of what we think the author is attempting, not based on whether or not we personally like the piece of writing. This requires practicing a mental flexibility that I think is valuable not just in criticism, but in life.

To return to Gould’s review, I want to be clear: I’m not saying that she had no right to write it. I’m suggesting that her criticism, and I think, her own experience, would have been strengthened if she had thought more about why Demi Moore was cast in the role. Filmmakers, like all artists, make deliberate choices as well as unintentional ones, and the latter can be just as illuminating. But I have to imagine that casting Demi Moore—who is considered, as Gould notes, “flawless” —and choosing to leave her “unblemished,” was a deliberate choice. What happens if we genuinely question the choices that confound us? Why Demi Moore? And why not age her a little more? An investigation of those questions leads in a telling direction, one that speaks volumes about the film’s intent. We find the art speaking back to us: Why am I so disturbed that someone who looks like Demi Moore would want to look younger? What does it say about the culture in which I exist and the ideals that culture lifts up for approval or rejection?

This is possibly a banal thing to say, but the magic of art is that it takes us outside ourselves. See Salman Rushdie writing about fiction: “In that miasmal ocean, we may simply float away from our hearts’ desires, and see them anew, from a distance, so that they may seem weightless, trivial. We let them go. Like men dying in a blizzard, we lie down in the snow to sleep.”

But in order to be freed from our particular selfness and allowed to float into the miasma of a more collective consciousness, where art lives, we have to be willing to let go of the hang-ups we’ve brought to the experience. It isn’t just good practice for film-viewing, it’s good practice; considering the intention behind other people’s choices, actions, words, strengthens our empathy. At the very least, it strengthens our criticism.🪱

This is excellent.