STANOPTICON

Celia Mattison on obsessive male violence, the victims swept into it, the society that permits it, and the woman unable to counteract it in 1981's The Fan.

This essay is the third of four in the Bookworm series, which focuses on horror films adapted from books. Bookworm is made possible by the Rocky Wood Memorial Scholarship Fund from the Horror Writers’ Association. Read the first essay here and the second here.

BY: GUEST WRITER CELIA MATTISON

"I hope you can't sleep and you dream about it

And when you dream, I hope you can't sleep and you scream about it

I hope your conscience eats at you and you can't breathe without me"

-Eminem, Stan

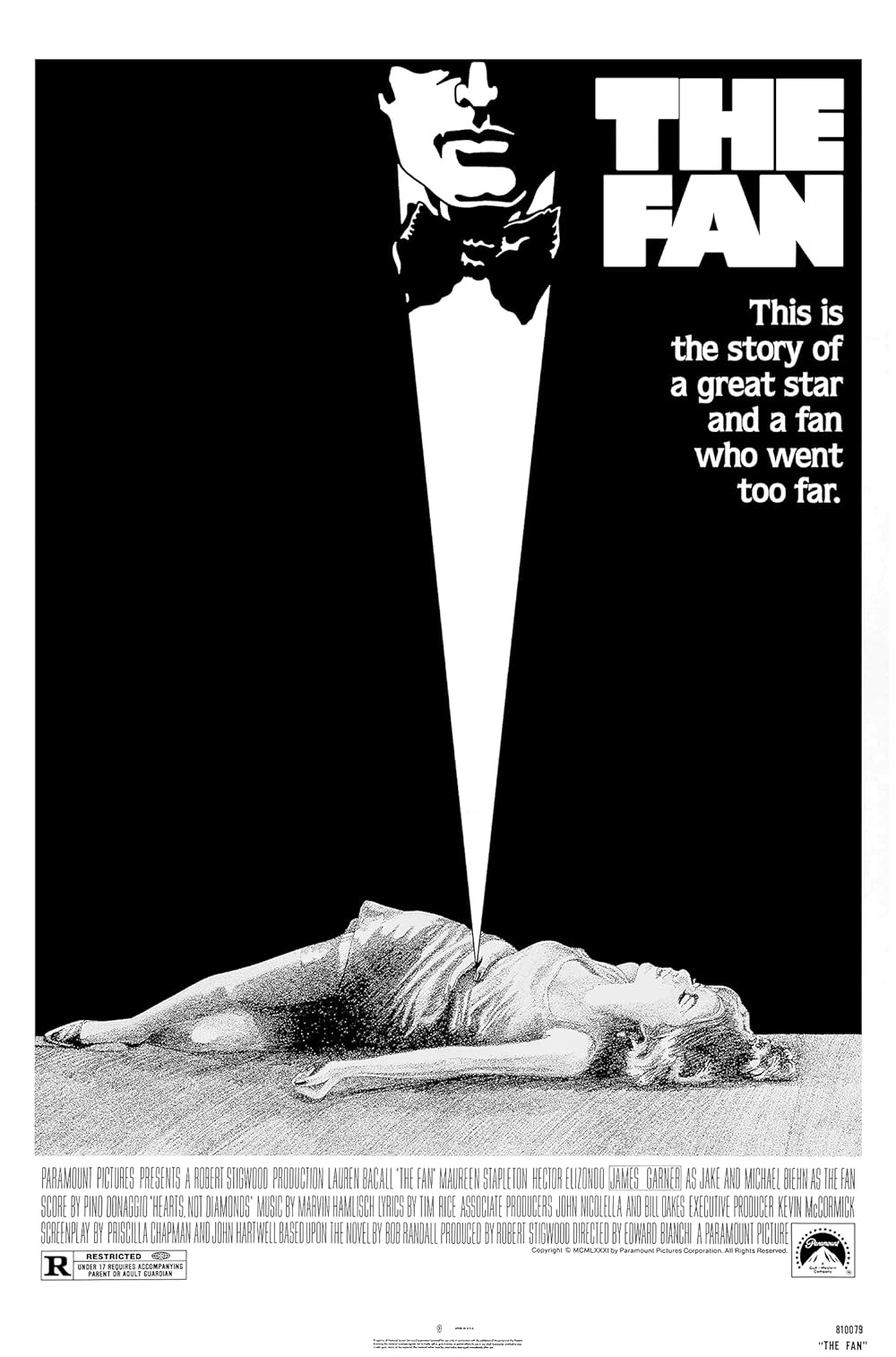

It seems surprising that Lauren Bacall and Michael Biehn ever knew each other, much less co-starred in a film. But in 1981, the titan of Hollywood Golden Age glamor and the understated action star at the center of Terminator and Aliens, came together in The Fan, a psychological thriller about a famous actress hunted by a violent stalker.

The Fan was a flop both critically and commercially. It’s based on the much better regarded but now out-of-print 1977 epistolary novel by Bob Randall, though neither iteration of The Fan has been much remembered. But before the word “parasocial” joined the popular lexicon, The Fan offered a prescient look at the nature of an obsessive fan culture that would develop over the next several decades into the robust twin industries of celebrity relatability and fandom.

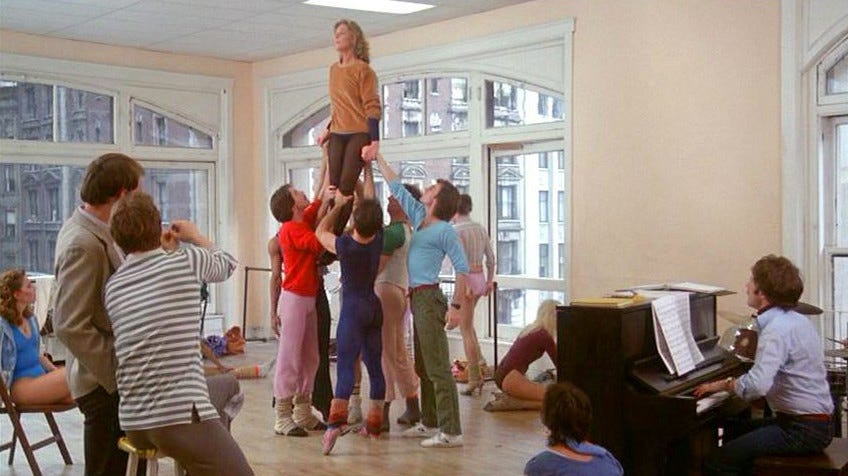

The Fan begins with Douglas Breen (Biehn), a young man who has started writing fan letters to stage and film actress, Sally Ross (Bacall). The letters start off creepy and quickly become frightening. Douglas professes his love for Sally and makes plans for them to consummate their passion, promising that he has the “necessary equipment” to please her. Sally’s friend and secretary of many years, Belle, handles the star’s cascade of fan mail, so Sally remains entirely unaware of Douglas for much of the story. She has her own concerns, namely rehearsals for a major stage musical1 that seems poised to revitalize her career, as well as navigating a reconnection with her noncommittal ex-husband Jake. When Sally doesn’t respond to his increasingly demanding letters, Douglas begins to target the people close to her, culminating in his plan to attack her on the opening night of her new musical.

Douglas’s behavior in The Fan is textbook incel behavior. His letters to Sally, demanding a response, are full of braggadocious claims about his physical form and endowment, the life he’d be able to offer her, and how he deserves a chance. He makes up a story about an entire store of customers applauding him after he tells off his boss, predating the “and then everyone clapped” internet meme by a good three decades. Listening to Douglas’s self-aggrandizing voiceover as he writes his letters feels like reading the SheRatesDogs Twitter page, except we never see anyone put him in his place. We get the sense that he has gotten away with a lifetime of entitled and antisocial, if not necessarily violent, behavior.2

Biehn portrays Douglas with an inflated, almost regal sense of self. With his coiffed hair and conservative sweater/button-down combos, he stands in sharp contrast to the hip record store coworkers who are the first to receive his abuse. Like a sniveling, spoiled brat grimacing through picture day, Biehn tunes the boyish vulnerability that made Kyle Reese into an iconic hero to a much darker frequency. One that remains uncannily familiar in an era rife with online male bullying.

In contrast, Sally is sharp and social, a faintly-drawn character that relies heavily on Bacall’s real life legendary career and charisma. While Sally is aware that her Hollywood career has faded, and that much of the stage work she pursues is frivolous, she delights in the pleasures of her matured career and the decades-long friendships she’s built throughout — "I always will love you,” she tells a friend in the novel. “[And] you, Belle, the ocean and the sky. What a rich life I've had!”

The shared intimacy of her correspondences with friends and colleagues is starkly different from Douglas’s unanswered rantings. What might have easily been a melancholic performance of middle-aged self-doubt is instead anchored in Bacall’s debonair ease and frosted edge, which makes her the perfect foil to the twitchily insecure Douglas. What initially drew Douglas into his fandom is not mentioned, nor is it important: what matters is that Sally’s untouchability and poise, which initially appealed to Douglas as proof of her icon status, now infuriates him.

The obsessed and murderous fan archetype is commonplace now3, but it was just beginning to emerge in popular imagination when The Fan was released, just a few months after the murder of John Lennon. Stalking is still seriously misunderstood and the police efforts in The Fan are almost comically pathetic, failing to catch Douglas even as he repeatedly breaks into Sally’s home and dressing room. No one, including the police, seems to quite grasp the danger Douglas poses, or even the idea that someone like Douglas could exist. When Douglas fakes his own death, Sally celebrates her freedom — no one considers that Douglas is simply a violent first iteration of a fan culture that is about to become an industry.

Douglas’s actions are shocking, but maybe less so today as they would have been to a 1977 audience. We not only have the benefit of 40 years of slasher horror and stalker dramas, but we also are living through a crisis of parasocial obsession. At the time I rewatched The Fan, Timothee Chalamet and Chris Evans were the most recent victims of parasocial meltdowns, as fan communities mounted online attacks primarily against the female partners of both actors. The public has not internalized any of the lessons we might have learned from the experiences of women who have suffered from the spotlight, such as Princess Diana or Britney Spears. The power of a fandom has been harnessed by stars like Nicki Minaj, who called upon her fans to harass reporters after they questioned some of her claims about Covid-19.4

Fan magazines and conventions have existed since mass media (what was the World’s Fair if not a massive con) but the emergence of the internet, and its fan communities, massively accelerated the growth of fandom as an industry. In the way that there are sports writers, there are now fandom writers, devoted to breathless coverage of the goings-ons in the Marvel Universe or Taylor Swift’s personal life. The proliferation of fandom that has led to an endless parade of sequels, reboots, and podcasts has also resulted in fan’s demands to access—even completely infiltrate—celebrity’s personal lives. We’re meant to contrast Douglas’s extreme isolation with Sally’s glamorous lifestyle surrounded by friends and colleagues.5 But today, her tiny squad of friends and collaborators seems quaint in comparison to the teams employed by even relatively minor celebrities to help them make public appearances, execute brand deals, and most importantly, remain relatable. We’re living in a post-Douglas age. We expect a certain level of rabidity from strangers, and an appropriate level of self-defense from public figures.

Many of Douglas’s hateful behaviors are abbreviated in the film adaptation; his paranoid tirades against queer people, in particular, are cut. The film keeps the scene in which Douglas cruises a gay bar to find a victim he can use to fake his own death. It’s easy to read this moment as that old homophobic trope — that Douglas is a closeted gay man whose self-hate and repression leads him to violence. The fact that Douglas’s victim looks strikingly like him helps with this pseudo-psychological reading. But in the novel, Randall, who was queer, makes it more explicit that Douglas’s homophobia is not a case of a man protesting too much. It’s just another example of his vicious bullying and regressive worldview: women who disagree with him are bitches, men who are attracted to men are degenerates.

In the novel, I see a queer political reading of Douglas as a physical representation of the endemic homophobic violence that went uninvestigated and underreported in ‘70s New York, the same epidemic captured in the 1970 novel Cruising.6 Police incompetence is even more deliberate and dramatic in the book, and the consequences are far more severe: Sally dies at Douglas’s hands. This interpretation is absent from the film, which mainly gestures to the novel’s queerness through an overtly camp musical. A hint crops up toward the end of the movie, in the final confrontation between Sally and Douglas, when she tells him “we’re sick of this reign of terror. I will not be a victim.” Perhaps Sally is speaking more literally of the friends who have also been victimized by Douglas, perhaps she is speaking of women in general who suffer male harassment. But perhaps this line is the film’s acknowledgment of its queer source material, and Sally’s recognition of Douglas not as an individual threat but as an agent of an unceasingly violent culture.

"We expect a certain level of rabidity from strangers, and an appropriate level of self-defense from public figures."

Here lies the most major difference in the storylines. In the film, Sally lives, turning Douglas’s own weapon against him when he hesitates to once again beg for her love. In the novel, he fatally shoots her on stage on the opening night of her play. Both endings are quite brief, even anticlimactic, because ultimately the story of The Fan is not about Sally’s or Douglas’s survival. The Fan is about obsessive male violence, the victims who get swept into it, the society that permits it, and the woman who is unable to counteract it.

Douglas’s delusions are an extreme example of a parasocial obsession, one that’s compounded by violent misogyny and entitlement. Today, Douglas could have a network of online communities feeding his obsession, through the manosphere that engages in public humiliation of women, through fan communities that abet stalking, through AI girlfriends that are trained to validate their users. As much as The Fan might seem quaint and corny, it was predictive of a parasocial behavior that would only increase with the dawn of social media.

“A lot of people feel close to me. People I don’t know and will never meet,” Sally explains to a cop. She had no idea how this pilfered intimacy — first desired, then feared — would evolve to fuel a devouring industry of its own.

Celia Mattison writes about film, fiction, and scuba diving. She is the author of Deeper Into Movies.

In the book, the musical is given the hysterically arch title, “So I Bit Him,” while the movie shifts to the more realistic but also more maudlin, “Never Say Never.”

Confirmed by the novel, which includes letters from his concerned mother that indicate Douglas has been receiving financial support from his family and has exhibited a pattern of bad behavior in the past.

My earliest memory of this archetype is in the video game The Sims Superstar (2003), the expansion that added an in-universe Hollywood and an obsessed fan that would stalk famous Sims. I would have been 10 years old.

Another thing that feels very of the time — constant platonic mouth-kissing between Sally and her male friends.

Also adapted into an even more fraught movie that I simply can’t get into right now.